Oregon is different.

And, it’s not just because of its rugged coastline, sweeping forests, and famously quirky culture. No, Oregon is politically different—and in ways that matter more than ever after this last election. While much of the country saw shifts that realigned political loyalties, Oregon stayed a bastion of blue. And it’s worth asking: why? Why is the Democratic majority in Oregon seemingly insulated from the kind of electoral accountability seen elsewhere? The answer lies in the deep urban-rural divide and the power of gerrymandering.

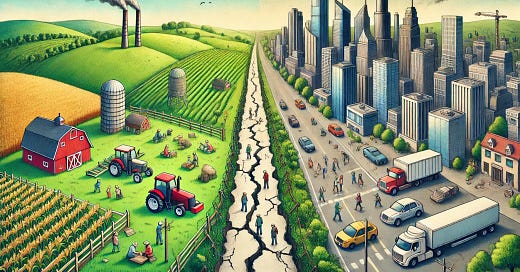

A Tale of Two Oregons

To understand Oregon politics, you have to understand the stark split between urban centers and rural communities. On one side, you have cities like Portland, Eugene, and Bend—places known for their progressive values, strong environmental focus, and support for social justice movements. On the other side, you have the vast expanses of rural Oregon, where people are more concerned with practical issues like land use, logging rights, water resources, and the ability to make a decent living without regulatory burdens strangling their communities. These are two very different worlds within one state, and they barely talk to each other.

Portland and Eugene dominate the political conversation in Oregon. These urban areas drive the state’s policies, and because that’s where the majority of voters reside, their voices carry the most weight. But when you look beyond these urban hubs, you see a different Oregon—one that feels increasingly forgotten and disenfranchised. Rural voters have watched as their concerns are consistently sidelined by legislators who answer to urban interests. Whether it’s restrictive environmental regulations that hinder rural economies or tax policies that make it hard for small businesses to thrive, rural Oregonians often feel like they’re left out of the discussion.

The FEMA BiOp: A Case Study in Disconnection

Take, for instance, the FEMA Biological Opinion (BiOp). The BiOp imposed strict requirements on floodplain development as a way to protect endangered species like salmon. While the intention behind the BiOp may have been noble, the reality is that it placed significant burdens on rural communities. Farmers and small-town developers found themselves facing new restrictions that made it nearly impossible to move forward with projects that were vital to their local economies. Urban lawmakers and environmental advocacy groups pushed for these changes, focusing on ecological preservation, but they did so without considering the real economic impact on rural residents.

This is a perfect example of how Oregon's urban-rural divide plays out in policy-making. For someone living in Portland, the FEMA BiOp might seem like a reasonable way to address environmental concerns. But for someone living in a rural community, it’s yet another regulation making it harder to make a living. The floodplain regulations meant higher costs, reduced property values, and endless bureaucratic hurdles—all of which add up to a serious disconnect between what urban policymakers prioritize and what rural residents need.

The Gerrymandering Problem

And this divide has only been made worse by gerrymandering—the art of drawing electoral district lines to benefit one political party. In Oregon, it means urban areas are carved into multiple districts, effectively drowning out the influence of more conservative, rural voters. Districts are drawn in such a way that the representation is disproportionately skewed in favor of the urban, progressive majority. Even if a rural community turns out in droves, they often find themselves lumped into a district where their voices are drowned out by the larger urban population.

This raises a critical question: Is it good for any state to be so insulated from the issues of the day because of political districting? When one party has a guaranteed hold on power due to gerrymandering, accountability takes a nosedive. Without the genuine threat of losing their position, elected officials have little incentive to address the concerns of all their constituents. This insulation means policies don’t adapt to the shifting needs of the entire state but instead continue to cater to a dominant segment—often urban, often progressive.

Look, this problem isn’t unique to Oregon. Across the country, similar patterns have emerged. Republicans have used gerrymandering in states like Texas to secure their positions and avoid being held accountable. It’s the same story but with different priorities—where Oregon focuses on progressive social issues, these states focus on limiting federal influence or cutting social programs. But the underlying problem remains: entrenched power, insulated from the will of the voters.

Insulation From Accountability

Remember the broader national trend from the last election? In many states, we saw shifts in voter loyalty because voters had the power to hold their representatives accountable. Politicians who were out of touch with issues like inflation, energy costs, and public safety got a reality check. Voters weren’t having it. But in Oregon, gerrymandered districts and urban dominance meant many voters—especially those in rural areas—didn’t have that same chance to push for change. The Democratic Party was able to maintain power by focusing on issues that resonated with their urban base, like reproductive rights, while largely ignoring economic concerns that mattered more to rural communities.

The result? A Democratic majority that doesn’t have to answer to everyone in the state. The political map here is built to ensure that certain voices always win, while others barely get a hearing. And that’s not just bad for party politics—it’s bad for democracy. Where there’s genuine competition between political parties, elected officials tend to be more responsive. They have to be, because if they aren’t, they risk being voted out. That’s not the case in much of Oregon, where gerrymandered districts mean the same political party has a lock on power, no matter how effectively they govern.

Moving Forward

So, what does this mean for Oregon’s future? It means that unless there are significant changes, the status quo will hold. Urban areas will continue to wield outsized influence over statewide policy. Policies that work for Portland—like increased environmental regulations or more social spending—will be prioritized, while rural areas get left in the dust, struggling under restrictive business environments and inadequate infrastructure investments. It means people in rural Oregon will keep feeling like their voices don’t matter to those in power.

For Oregon to really move forward, it needs to address the imbalance in its political system. The urban-rural divide is always going to be there—it’s part of what makes Oregon what it is. But when gerrymandering exacerbates that divide, it creates a political environment where some voices are always left out. Redistricting should be about fair representation, not just cementing power. Until that changes, Oregon will stay stuck, with one part of the state thriving while the other is left behind, with no way to hold their leaders accountable.

It’s time for Oregon to take a hard look at how it draws its political lines and think about how to create a system where all Oregonians—urban and rural—feel heard. Accountability shouldn’t depend on your zip code.

What do you think about the rigging of elections since 1986 when the mail-in ballot was voted in? Check it out. Are you aware of the following?

Oregon became a state in 1859. From 1859 to 1986 Oregon had 13

Democrat Governors, 20 Republican Governors and 1 Independent. That's 38%

Democrats, 59% Republicans and 3%Independent. Since 1987, with the change to

only mail-in ballots, we have had 100% Democrat Governors (6). Also

interesting, prior to 1987, we never had 6 Democrat governors in a row but we did have 6 Republican governors in a row. Makes you go ummmm... What are the odds of this happening?

This is why my family left Oregon. We didn’t want to raise our children in a state where the government actively wants to teach my children to hate their parents’ values.